SINGAPORE – To bolster the skillset capability of Singaporeans across various stages of life, SkillsFuture Singapore has launched a campaign to drive greater awareness and understanding of SkillsFuture initiatives. Ogilvy & Mather Singapore was the creative agency for the campaign and the TVCs were launched this week on Mediacorp Channel 5 and Channel 8.

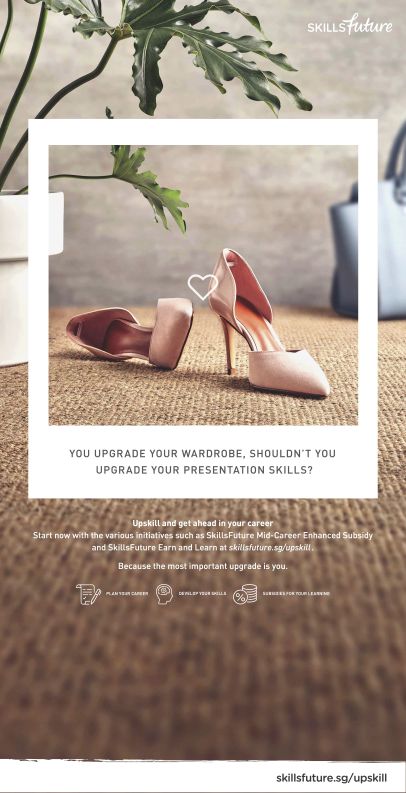

The campaign’s concept, which underlines the fact that ‘The Most Important Upgrade Should Be You’, adopts a simple metaphor that conveys a powerful message – emphasizing how upgrading your professional skills is of equal, if not greater importance, than upgrading your everyday necessities. Resembling retail and lifestyle advertisements, the team took the unconventional approach of capturing the audience’s attention by appealing to their ‘consumer’ instincts via an engaging fashion retail-style look and feel.

Brenda Han, Managing Partner, Ogilvy & Mather Singapore, said, “To motivate people to embark on their journey of lifelong learning, we drew a simple parallel to the items in their life that they upgrade frequently, rather than themselves. We want to influence those who have not taken steps to upgrade their professional skills and emphasize that the only way to stay relevant in today’s competitive and ever-changing job market is to keep learning and growing your skills.”

Patricia Woo, Director, Corporate and Marketing Communications, SkillsFuture Singapore, said, “Investing in yourself is an important and lifelong process. We hope this campaign will prompt people to re-view their learning and career goals and realise that they need to upskill and reskill to stay relevant and achieve their potential. There is a wide range of SkillsFuture programmes available for individuals regardless of the stage of their careers that will enable them to deepen their skills and grow themselves.”

As part of the launch, a series of ads and TVCs will run across various channels including a dedicated campaign landing page and social media platforms including Facebook, Instagram and Youtube.

CREDITS

Project title: The most important upgrade should be you

Client: SkillsFuture Singapore

Creative Agency: Ogilvy & Mather Singapore

Executive Creative Director: Melvyn Lim

Account Management: Brenda Han, Ng Shin Yi, Sameer Rasheed

Creative Director: UmaRudd Tan, Loo Yong Ping, Xander Lee

Senior Copywriter: Augustus Sung

Senior Art Director: Nico Tangara

Strategy: Frederick Tong, Trisha Santhanam

TVC Production House: The Prosecution Film

Director: Warren Klass

Producers: Aundrea Bligh, Caroline Frances

Print Production House: Shooting Gallery

Exposure: Print ads, TVC, cinema, OOH, digital banner, social media