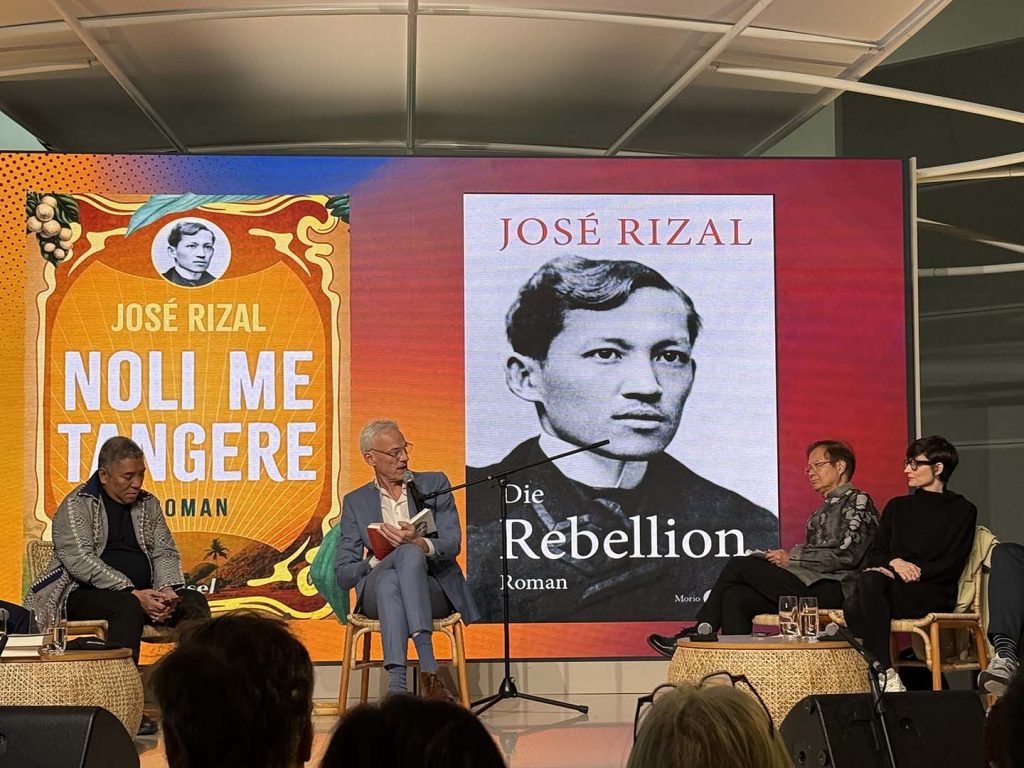

FRANKFURT, GERMANY – At the Philippine Pavilion of the Frankfurter Buchmesse, a full audience gathered to revisit José Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, the novels that stirred a revolution, and ultimately cost Rizal his life in 1896. But this was no simple celebration of national heroism. The panel, titled “Benedict Anderson and José Rizal”, unfolded as an exploration of how translation: linguistic, cultural, and historical continues to shape our understanding of nationhood.

Moderated by Lisandro Claudio, an intellectual historian and professor at UC Berkeley, the session brought together two of Rizal’s most passionate interpreters: Ambeth Ocampo, the country’s premier public historian, and Patricio N. Abinales, the recently retired University of Hawai‘i scholar who studied under Benedict himself.

What emerged was a rare and intimate portrait not only of Rizal and Anderson, but of the creative act of re-reading and re-translating a nation’s story.

Benedict Anderson and the imagined nation

Benedict Anderson (August 26, 1936 – December 13, 2015) was an Anglo-Irish political scientist and historian who lived and taught in the United States. He is best known for his 1983 masterpiece, Imagined Communities, one of the most influential works of the 20th century on nationalism and cultural identity. In that book, Anderson defined a nation as “an imagined political community — imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign.” He argued that nations are not born from bloodlines or geography, but from shared stories, the narratives people tell and read together, through language, literature, and print culture.

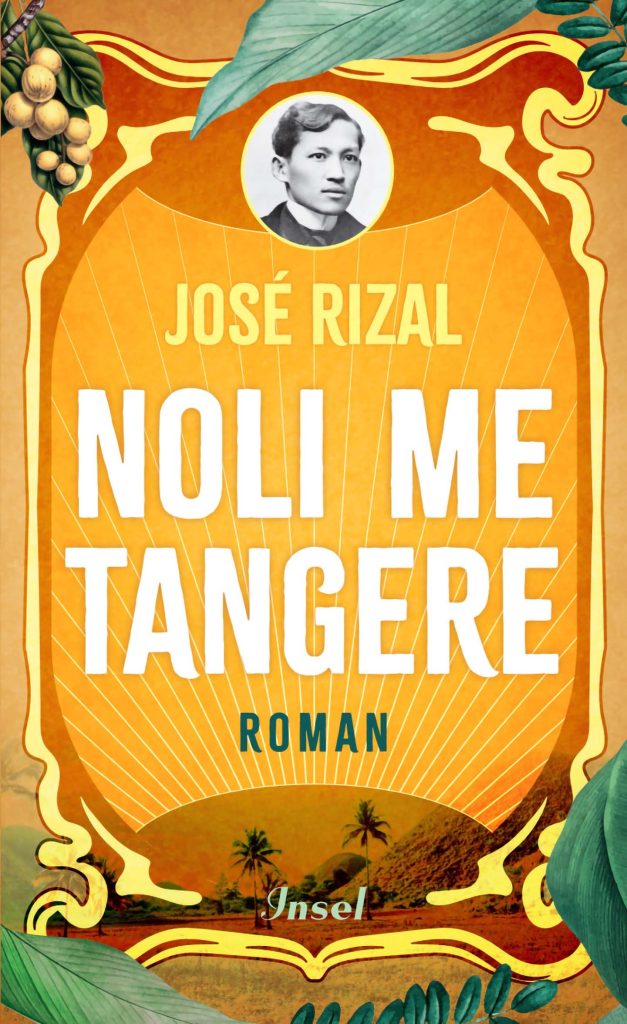

Benedicts’s own fascination with José was deeply personal. He saw in Rizal’s novels, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, a literary act of nation-building. For Anderson, Rizal didn’t just write about the Philippines; he imagined it into being.

The world according to Ben and Jose ‘Do you think Rizal dreamt in color or in black and white?‘

That, according to Ambeth Ocampo, was one of the first questions Benedict Anderson ever asked him. It was the kind of question only Anderson could ask – playful, irreverent, and profound. The political scientist behind Imagined Communities, one of the most cited books in global social science, was fascinated not only by Rizal’s politics but by his imagination, by how he dreamed the Philippines into being.

Ambeth recounted how Benedict, who first met him in the late 1980s, insisted on sitting in his undergraduate Rizal class at the University of the Philippines. “He was more interested in Rizal than my students were,” Ambeth laughed. The two would later travel together to Calamba, to Rizal’s childhood home, to Biak-na-Bato, and even to a Rizalist church in Laguna where the hero is literally enshrined on the altar.

Anderson’s curiosity was limitless, even mischievous. He studied Spanish just to read Noli and Fili in their original language. He wanted to feel Rizal’s rhythm, hear his laughter, and uncover the wit and irony that often disappeared in English translation.

“He wanted to see things beyond what you’re seeing, to look from another angle,” Ambeth said. “That’s what made Ben’s reading of Rizal so alive.”

The laughter that disappeared

For Patricio Abinales, who studied under Benedict at Cornell, translation was central to Anderson’s obsession with Rizal.

When Benedict reread Noli Me Tangere in English, he found it “oddly sanitized.” The translations stripped away the European setting, erased the bawdy humor, and muted Rizal’s laughter, that subversive laughter that mocked friars, bureaucrats, and the absurdities of colonial life.

“One of the first questions Ben asked us was, ‘Where is the laughter coming from?’” Patricio recalled. “He said, when you read Noli in German, you don’t ask who is laughing, you ask where the laughter comes from?”

That laughter, Benedict believed, was the key to José’s critique. Through humor, Filipinos could recognize their own corruption mirrored in colonial society. The friars, the politicians, the pretenders, and laugh their way toward national self-awareness.

But by the mid-20th century, that laughter had been lost. Translations like Leon Ma. Guerrero’s 1960s Noli Me Tangere, designed for a global English readership ironed out the slang, the curses, the double entendres. What remained was a polished José, stripped of his mischief.

“The Philippine state pushed Rizal farther into the past,” Patricio said. “We forgot that the corruption he mocked in Spanish times, the bastards of the friars, are the same bastards we have today. The past is not the past. It’s still here.”

Rizal in translation

This tension between readability and fidelity animated the panel’s most spirited exchange.

David Guerrero, son of translator Leon Ma. Guerrero, rose from the audience to defend his father’s 1960s translation. “Anderson judged the translation by 1990s standards,” he noted. “In the ’60s, translators prioritized readability for mass audiences. By the ’90s, we wanted authenticity. It’s unfair to judge one era by the values of another.”

Ambeth agreed, noting that “Guerrero wrote his version for a specific audience and time.” He added that each translation reveals more about its era than its author. “Our challenge now,” he said, “is to find a translation that brings us closest to Rizal’s Spanish and yet remains readable to the 21st century Filipino.”

He lamented that the Derbyshire translation, long used in schools, erased all the earthy, “bastos” bits, from the village gossip to a man caught mid-defecation. Even food, “different types of fish, how they’re cooked”, was cut out.

“Translation is not just linguistic,” Ocampo said. “It’s cultural. When you clean up Rizal, you clean up the Philippines.”

The impish Rizal

Benedict loved José not because he was perfect, but because he was impish — playful, ironic, and subversive. He admired how Rizal wrote in Spanish yet peppered his prose with Tagalog words, puns, and curses that only Filipinos could truly understand.

“It was Rizal’s way of saying: we can read you, but you cannot read us,” Patricio said. “That was his revenge on empire.”

Even the Spanish authorities recognized the power of Rizal’s pen, a power so dangerous that it led to his execution in 1896. But Anderson saw beyond martyrdom. For him, Rizal was the first postcolonial writer of Asia, a man who laughed at empire even as he dismantled it.

In Imagined Communities, Anderson argued that nations are “imagined” through language and print through shared stories and shared laughter. Rizal, in that sense, imagined the Philippines before it ever existed.

Benedict affectionately called him “Lolo Jose”, the intellectual grandfather of Southeast Asian nationalism.

Beyond translation: Imagining again

In the final moments of the session, Lisandro asked the question that hung over the room: Why did Benedict, who admired Indonesia’s fiery revolutionary Tan Malaka, fall in love with José, a liberal reformist who rejected violence?

“Maybe,” Ambeth mused, “because Rizal fought with ideas. With literature.”

That, perhaps, is what Benedict found irresistible: the power of imagination over ideology, laughter over rage, translation over tyranny.

As the audience at the Frankfurt Book Fair dispersed, one could sense that the conversation was far from over. The question remains: How do we make Rizal laugh again? in Tagalog, in English, in German, and in doing so, help Filipinos imagine themselves anew?

Ambeth Ocampo once found an unpublished Rizal manuscript mislabeled at the National Library – 245 pages of Makamisa, the Tagalog novel Rizal never finished. Its first scene? A priest rushing through Mass, and the whole town gossiping about his bad mood.

Even unfinished, Rizal was still laughing and teaching us to laugh at ourselves.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s where nationhood begins.

Key English translators of Rizal’s novels

- Charles Derbyshire (1912): The first complete English translations of Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo. Faithful but prudish, omitting colloquial humor and local flavor.

- Leon Ma. Guerrero (1960s): Elegant, readable translations for global audiences; streamlined Rizal’s ornate Spanish prose for mass appeal.

- Ma. Soledad Lacson-Locsin (1990s): Sought to restore Rizal’s original rhythm, structure, and cultural nuance, closer to the Spanish texts.

- Harold Augenbraum (2006) translations of Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo are Penguin Classics versions noted for being well-translated for an international readership.