For as long as there have been children, there has been some form of tune hummed to put them to sleep.

MANILA, PHILIPPINES — Children’s bedtime was largely ritualistic before it turned occupational. In the city, a working mother would have time when the clock strikes 9 in the evening. She would put her child, sandwiched between bolster pillows, or accompanied by stuffed animals for softness and comfort. By the side table, a tablet is streaming CoComelon’s channel about the direction of the wheels on the bus or Baby JJ’s (the hero of every video) abject rejection to sleep. The electronic device trumps the soporific effect of a mother’s hum.

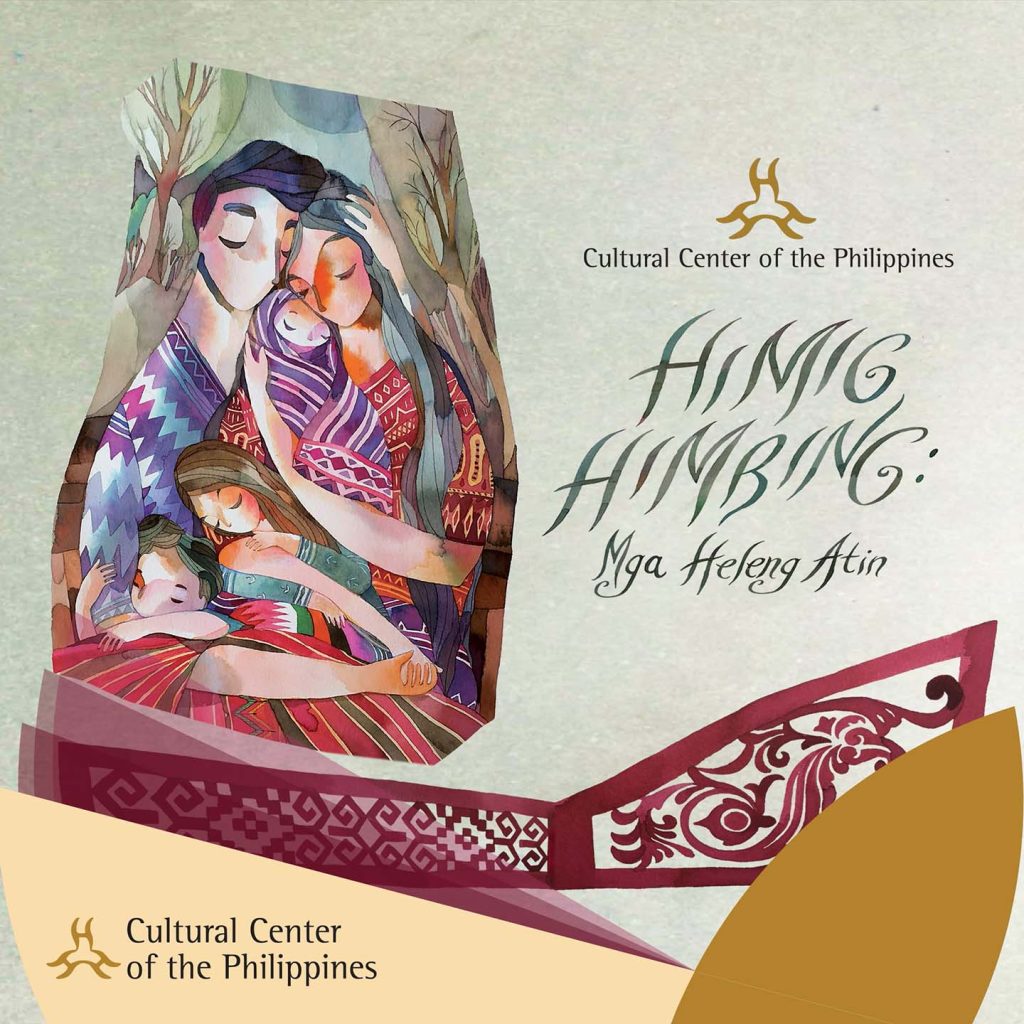

“Any song can be a lullaby,” Sol Trinidad, the ethnomusicologist and curator of the songs behind Himig Himbing, told me. The project of the Cultural Center of the Philippines to bring indigenous lullabies to the regions took shape during the pandemic lockdown and befittingly as it was a period of prolonged homestay with the family and deliberate bids for connection of parents isolated from their children.

Photojournalist Hannah Reyes Morales documented this among other scenes of what she calls safe-space making in her project “Living Lullabies.” From mothers in war-torn areas to children in the most unlikely cradles, the collection opens a window beyond the imagery of a commercial-manicured mother with a babe in her arms.

Time spent, time carved

The basic components of these lullabies is as common as those of folk songs with easily memorized melody, not necessarily languid or somber but as long as it is inducing of tranquil sleep.

“The time that the person sings the lullaby to the child is also like a me-time to process whatever it is that they’re going through,” Sol explained.

Beyond function, lullabies are plucked from history but reflective of a caregiver’s reality. Although it is in the presence of a loved one, the singing of lullabies is a solitary activity.

“It’s not always about the child. It’s really about the caregiver, the nurturer, the person watching the child.”

It’s a notion stemming from the children as its subject that lullabies must talk of the moon and the sweetness of dreams. Yet in reality, even the most popular lullabies are not sanitized to be child-friendly, and that, anybody can be entrusted with the child: siblings, grandparents, even neighbors.

This is demonstrated by “Bata Alimahi” (Cebuano lullaby) which, despite its swinging rhythm and playful vocals, is sung by a mother who asks the grandma to safe-keep her child out of her yearning for her freedom when she was a single woman. (Kay ako mubalik sa pagkadalaga.)

Here, Sol pointed out that the singer talks about the context of being a spouse, translating its lyrics, “being married is difficult. I bring the rice home, and my husband nagborobinanday — is the action of somebody who is lasing, who is a drunk.”

Himig Himbing

In Pangasinan where the Himig Himbing: Oyayin Niyanakan kicked off Galila Arts Festival 2024, “Ligliway Ateng” talks about children as heaven’s gift to salve their parents’ sorrow and state of exhaustion. The rest of its lyrics gives an emphasis on daughters’ behaviors and their urges for material things.

In the course of her research, Sol found that the popularity (or the waning) is indicative of the strength and decline of language. Some Pangasinense do not know the particular lullaby at all and some are familiar with the tune but not its lyrics such as its director for the music video Christopher Gozum.

“There are words that are not in use anymore. Old words — these are words that are tied to language which keeps us rooted.”

“Ligliway Ateng” is an example of how songs are elevated into folk song status. Originally composed by Pablo Mejia for his sarswela “Sileb na Tubonbalo,” the lullaby made its way to the consciousness of the region’s population.

This third year of Himig Himbing resulted in a book to accompany the album, regional tour, and a workshop for school teachers, parents, social workers, and counselors. In it, they were taught about creative expression in the arts facilitated by physician and children’s book author Dr. Luis Gatmaitan, artwork and book designer Beth Parrocha, and Sol herself.

One thing that became apparent from the workshop is how non-restrictive lullabies can be. Some of the attendees suggested religious songs when they were asked what they recalled from their childhood — Marian songs, especially, as these are what’re familiar to their nurturers and served the purpose.

“Any song, as long as it works, can be a lullaby. If your child can sleep to the tune of ‘Jingle Bells’ because of the cradling, then that’s a lullaby. If your child can sleep to the motion of ‘We Will Rock You,’ then that’s a lullaby.”

Gonon Klukob Tumabaga

Sol’s brief was this: create a selection of lullabies that are a good representation of the different ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines. From there, it was a matter of narrowing down without being Luzon centric.

On a trip to Mindanao, I have watched the agung played five times. These are huge bossed gongs up to 45 cm in diameter that are a prized possession for families and played in an ensemble of kulintangs, falimak, and other idiophones for performances.

Twice, it was suspended from a bar along with other flat gongs struck either at the knob at the center of the face of the gong and at its rim. The rest of the times it was positioned sideways on the ground hit with a padded mallet.

These gongs were the subject of a Blaan lullaby: Gonon Klukab Tumabaga. Monotonous and almost singsong, it paints a picture of the narrator’s joy and pride when he would play with the gong but in his absence on a journey to the mountains, someone else played with the gong and he shall not touch it anymore. (Doni balo mi-osa banayan la kudon budmikong mataw)

Gongs, along with water buffaloes, horses, and necklaces, are used to negotiate bride-prices in the kafni (gift-giving) in the Blaan culture and consistent with other indigenous groups, gongs are played by the men. Although themes of ownership and consent are in the undercurrent, this lullaby exemplifies how some are spared from the whimsy and fancy elements and lets the narrative take precedence.

Didacticism

Lullabies are cyclical in nature and structure. When it’s not used to lull children, it can be lively and used to a didactic effect — descriptive of the place’s landscape, societal conditions, or passing of time such as the Tagalog “Lubi-lubi” which enumerates the months of the year.

A lullaby hailing from the Mansaka talks about the passing of a child who was not brought to the hospital. Hence, Sol infers that the place can be too far off from the city or lacking in doctors, or telling of the economic standing of the family. It can contain multitudes, as in “real issues in real life of the communities of the indigenous groups.”

Sometimes, songs talk of the geography of the place, the difference between a river’s name on the map versus how it’s called in the people’s vernacular.

Renewing nostalgia

As a pacifier of fears, lullabies tell more of the singer’s immediate concerns than the child’s. The potency of imprinting on children lies on the singer. One of the most widely recognized lullabies, “Sa Ugoy ng Dugan,” puts to music the nostalgia and yearning to being childlike once more.

Sol chalks its prominence up to the names behind the song: National Artist for Music Lucio San Pedro with lyrics by National Artist for Literature Levi Celerio but also to of its iterations throughout the years from choral arrangements and repeated performances.

Some of its notable uses are being the theme song for Behn Cervantes’ Sakada (1976), popularization from UP Madrigal Singers and UP Concert Chorus in the ’60s, and arrangement for the Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra and Ballet Philippines at the composer’s conferment of the National Artist Award is 1991. It also became nationally ingrained as well thanks to a ’90s baby powder commercial:

The return to home

With the sway of the hammock comes the reassurance to the infant which is a recurring theme to most lullabies: The Visayan “Ili-Ili Tulog Anay” and Boholanon “Tingkatulog.”

Hailing from the regions, the songs are now being returned and re-introduced through Himig Himbing. The album’s selections arranged by musical director Krina Cayabyab expanded through music videos by acclaimed film directors.

“Maaari nating ibalik ang mga hele na ito na maging bahagi ng ating ng ating pang-araw-araw na buhay nang sa gayon ay lalo pa nating makilala ang ating mga sarili bilang Pilipino,” said CCP artistic director Dennis Marasigan.

(We can revive these lullabies as part of our everyday lives in order to realize our identities as Filipino.)

During the Antique leg of the regional tour, native filmmaker Arden Rod Condez who directed Bata Alimahi’s music video commented on how special the homecoming is.

“Seeing my kasimanwas (someone from the same region) react to the films I’ve made is always rewarding. My music video for Himig Himbing’s ‘Bata Alimahi‘ is no exception. The song, despite its somewhat painful lyrics is danceable. Seeing the audience bob their heads to it made me smile. I hope it sparks their interest in discovering more lullabies from other regions and unearthing additional songs from our place, aside from ‘Ili-ili Tulog Anay‘ and ‘Dandansoy.’”

To further multiply its impact, the regional approach of Himig Himbing for educators carry the potential for not just promotion, but understanding and appreciation. On the magnitude of the teacher’s role and responsibility to aware an expose children to the existence of the songs, literature, stories, and dances, Sol added, “Hopefully, teachers can make use of them as part of their resources or materials to introduce language, to introduce a way of life.”

Consciousness

What exactly happened to lullabies and why did we stop hearing them?

Sol explained, “Years ago, parents, let’s say mothers, when they sing the child to sleep, it is because gusto nilang mag-siesta ‘yung bata. Ibig sabihin, the mothers had time to put their child to siesta. In the urban setting, where are the mothers? Even in the provinces, the kids are in school as early as five years old so halos wala na ‘yung practice of singing lullabies. It’s utilitarian, but like many of our creative practices like singing, it’s there because it’s valuable.”

(Years ago, parents, mothers sing the child to sleep because they want them to take their afternoon nap which means they had time to do that. In the urban setting, where are the mothers? Even in the provinces, the kids are in school as early as 5 years old so lullabies as a practice is in decline. It’s utilitarian but like many of our creative practices like singing, it’s there because it’s valuable.)

These are valuable timestamps of our history. -Sol Maris Trinidad, ethnomusicologist

By giving gravity to the social importance of lullabies, the consciousness becomes two-fold: the one being instilled on the child and the effort it imposes on entities and organizations like the CCP. In the same breadth, the ethnomusicologist said, “The child is sleeping but hopefully, sana paglaki n’ya, mulat s’ya sa mounding kung sa’n n’ya kinagisnan, mulat s’ya kung sa’n s’ya galing.” (The child is sleeping but hopefully when they grow up, they are conscious about the world where they were raised in, where they came from.)

CCP Supervising Arts and Culture Officer and Himig Himbing Project Director Lino Matalang Jr. commented on its significance, “Ang Himig Himbing ay humuhubog sa ating musmos na alaala at patuloy na yumayakap sa ating pagtanda. Layunin nito na ipadama ang makabagong henerasyon na muling mahumaling sa himig na binuo ng kalinga at pagmamahal, at buhayin at ipalaganap unit ang heleng sariling atin.”

(Himig Himbing shapes our youthful memory and embraces us well into our adulthood. It beckons the new generation to be fond of the melodies crafted with love and care and give life and pass on lullabies of our own.)

While in practice, it’s more demanding to sing than a quick goodnight and prop of YouTube to lull children, lullabies convey more than sonority. It’s that which comes in many names: oyayi in Tagalog, ili-ili in Panay and Negros, duayya in Ilocos, baliwayway by the Ilongot, wiyawi by the Kalinga, almalanga by the Blaan; but all the same as described in “Ugoy ng Duyan,” awit ng pag-ibig, songs of love for whom it’s sung to.